Question[]

The biblical understanding of divine image represents a radically and deliberately different approach to this phenomenon within the ancient Near East; no analogues or precedents to it can be found in other ancient Near Eastern cultures.” How would you react to this statement? In answering this question, describe at least two contrasting scholarly proposals regarding aniconism. You must also use sources beyond the Bible, like archaeology and what we know about the rest of the ANE in your answer.

Answer[]

Anthropomorphic cult statues were a major focus of religious practice in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Levant. These images provided a focal point for worshippers to experience the deity ‘face-to-face’ in the context of religious festivals and temple service. Deities were thought to be manifest in their cult statues, where they could taste and smell votive offerings and hear worshipper’s prayers.

Archaeologists have yet to find a cult statue from Israel, but only a few cult statues have been found in Mesopotamia and Egypt.

The meaning of aniconism is a slippery thing. As David Freeburg points out, “Usage of the term [aniconism]—and therefore the notion itself—veers from implying the absence of imagery tout court, to the absence of figurative imagery, and then—in an apparently arbitrary step—to abstinence from figuring what is regarded as spiritual” (54).

There was no one biblical understanding of divine images. The various law codes, for example, prohibit different things:

Decalogue Exod 20:4 = Deut 5:8 “You will not make a hewn image (pesel) whether in the form of anything that is in heaven above or on earth below or in the waters below the earth.” [Only hewn images are prohibited.]

Covenant Code Exod 20:23 “You will not make gods of silver alongside me (ˀittî) nor will you make gods of gold for yourselves.” [This verse seems to suggest that Yahweh had the exclusive right to be represented in cult statues]

Holiness Code Lev 19:4 “Do not turn to idols (hā-ˀĕlîlîm) nor make cast images of gods (ˀĕlōhê massēkâ) for yourselves!”

Holiness Code Lev 26:1 “You will not make idols (ˀĕlîlîm) or a hewn image (pesel) for yourselves. And you will not erect a standing stone (maṣṣēbâ) for yourselves or put a figured stone (ˀaben maśkît) to worship it.”

Covenant Curses Deut 27:15 “Cursed be the man who makes a hewn image (pesel) or cast image (massēkâ), abhorrent to the lord, the work of the hands of the artisan and sets it up in secret.”

‘Ritual’ Decalogue Exod 34:17 “You will not make cast images of gods (ˀĕlōhê massēkâ) for yourself.”

Bronze Bull from Samaria

These laws are normative. The proliferation of prohibitions suggests that images continued to be made, which fits archaeological and biblical data.

Excavators found a bronze bull figurine dated to ca. 1200 b.c.e. at Dothan near Samaria in what is believed to be a cult site. It is unclear, however, whether this site was Israelite at this time period. Nevertheless, the figurine recalls the bull statues that Jereboam installed in Dan and Bethel (1 Kgs 12:28-29).

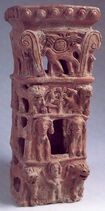

The first Tanaach cult stand

The two Tanaach Cult Stands (10th c. b.c.e.) feature a wide variety of imagery. One of them depicts a naked, female figure (perhaps Asherah) flanked by lions, cherubim, a tree flanked by rearing caprovines, and a horse or bull calf carrying a sun disk on its back, which some scholars have identified with Yahweh. The other lions, cherubim, a tree flanked by rearing caprovines, and a male figure strangling a snake, which some scholars have interpreted as Baal or Yahweh fighting Leviathan.

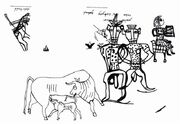

A scene from the Kuntillet 'Ajrud vase paintings

The 8th century vase paintings from Kuntillet ‘Ajrud feature rearing caprovines flanking a stylized tree, a lion, a seated lyre player, a cow nursing its calf, a line of worshipers, and a bes and bestet figure.

Israelite scarab seals depict a wide variety of animal and human figures throughout the Iron Age (See Keel), some of which are likely to be gods. Only in Iron IIC do aniconographic seals become commonplace.

6th c. B.C.E. Pillar figurines from Judah.

Pillar figurines appear in domestic contexts from the 10th-6th centuries b.c.e. and become increasingly common in the Iron IIC. They most likely represent a goddess.

Two owl-like figures, perhaps representing the spirits of the dead, are carved into the wall of an Israelite style tomb at Tell-Eton from the 9th-8th century.

Tomb carvings from Tell 'Eton

Excavators at Hazor found two male figurines made of metal dated to the 11th and 9th centuries b.c.e. The 11th century figure is of the ‘enthroned god’ type known from Ugarit.

It is unclear which of these visual representations would have been prohibited in the different law codes.

In DH, Hezekiah and Josiah don’t eliminate all visual representations, only the ones considered non-Yahwistic by Dtr (e.g., the Asherah pole and the bronze serpent). Akhenaten also eliminated certain forms of visual representation during his reform. So there may be a correlation between religious reform and the prohibition/elimination of specific visual representations.

Specifically anti-cult image rhetoric doesn’t appear until the Exilic period where it occurs alongside monotheistic rhetoric as a reaction to Mesopotamian religious practices:

e.g., Jer 10; Jer 50:2; Ezek 22:3-4; Hab2:18-20; Isa 44:19; Isa 42:7

Exilic editors of the DH could have projected these biases back onto earlier periods. This can be seen most clearly in the story of Micah (Jud 17:1-5). Nothing in the story itself suggests that Micah’s image (pesel û-massēkâ) were considered improper, but the later insertion of the monarchic refrain in Judges 17:6 does.

Ron Hendel summarizes the typical scholarly reasons given for Israelite Aniconism as follows:

1) Yahweh cannot be magically manipulated (Zimmerli).

It is unclear how divine images facilitate magical manipulation. Hendel suggest that Zimmerli had divination in mind, but divination is more concerned with discerning the divine will than coercing divine action.

2) Yahweh is transcendent (von Rad).

Mesopotamian deities were also thought to be transcendent (i.e. beyond the ken of mortals) and could still be represented visually.

3) Yahweh is the god of history and representing him visually would imply constraints on his power to act (ˀĕlōhê massēkâ).

Marduk, Asshur, and other deities act in history, but are still depicted visually.

4) The use of images is a Canaanite religious practice that the Israelites rejected (Keel).

The Israelites were Canaanites, so it is still necessary to explain why they rejected an earlier practice.

Hendel suggests that the Israelite aniconism stems from Israel’s ambivalent attitude toward kingship. According to him, the image of the enthroned god that was popular in Late Bronze Age Canaan was based on the image of the enthroned king. Because the early Israelites were egalitarian, they rejected both royal and divine imagery at the same time. Hendel’s theory does not explain the prohibitions on images in general.

According to Thomas Levy, the Israelites prohibited ‘molten gods’ to distinguish themselves from the Edomites, who were master coppersmiths, in the process of ethnogenesis. His theory may explain the prohibition on cast images of god (massēkâ).

Mettinger argues that the Israelite’s use of standing stones (maṣṣēbôt) evolved into a more general aniconism. But standing stones are iconic—they are a visual representation of the deity. Furthermore, standing stones existed along side other forms of visual representation in both Israel and other Ancient Near Eastern cultures, such as Mari. They did not represent a distinct stage in a move toward aniconism.

Bibliography[]

Curtis, Edward M. “Idol, Idolatry.” In The Anchor Bible Dictionary III., edited by David Noel Freedman, 376-381. New York: Doubleday, 1992. 376-381

Freedberg, David. The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989.

Hendel, Ronald S. “The Social Origins of the Aniconic Tradition in Early Israel.” CBQ 50 (1988): 365-382.

Keel, Othmar and Christoph Uehlinger. Gods, Goddesses, and Images of God in Ancient Israel. Translated by Thomas H. Trapp. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1998.

Levy, Thomas M. “Pastoral Nomands and Iron Age Metal Production in Ancient Edom.” In Nomads, Tribes, and the State in the Ancient Near East: Cross Disciplinary Perspectives, edited by Jeffrey Szuchman, 147-177. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Mettinger, Tryggve N.D. No Graven Image?: Israelite Aniconism in Its Ancient Near Eastern

Context. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International, 1995.

Schneider, Tammi J. An Introduction to Ancient Mesopotamian Religion. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2011.